As Indonesians took advantage of faster, cheaper and more powerful mobile phones and networks, they also started dipping their toes into mobile games.

The success of titles like Tahu Bulat on mobiles and smartphones began a gaming boom that started in 2016 and continues to this day; as of 2021, Indonesia’s video game market is sixteenth largest in the world and worth US$1.92 billion. Despite these successes, sustainability isn’t guaranteed; speaking with Tirto, Eka Pramudita of Mojiken Studio estimated the average lifespan of a local development studio to be only five years, citing development costs and standards as primary reasons as to why businesses fold so quickly.

With that prophecy in mind, it’s no wonder that local developers tend to frame the industry through a lens of failure. To ensure continued success within Indonesia, studios need to not only create games for mobile phones but for other, more complex platforms, and that requires both digital know-how and the funding to make it all happen.

As two local developers succinctly put it, they need the opportunity to create a work and potentially fail in doing so, yet be secure enough to be in a position to use the experience to build bigger and better things.

Humble – and different – beginnings

Toge Productions has easily bested that average five-year lifespan, starting back in 2009 when now-CEO Kris Antoni Hadiputra joined forces with a friend to create browser-based games including the runaway hit Infectonator. Hadiputra created the titles for playback using Flash, an Adobe multimedia platform that’s since been discontinued.

The company’s name draws inspiration from an Indonesian word meaning “bean sprout,” and is a wholly accurate representation of its origins. Infectonator’s sudden success meant Hadiputra and his partner turned from new graduates messing around with game development into a development studio proper.

The trend continues to this day; a makeshift office in a garage made way for a fully-fledged office in Tangerang. Kris himself transitioned into a businessman, not only managing a development studio but a small publishing arm by 2015. He’s added the Toge Game Fund Initiative, a source of funding for fellow developers, into the mix in recent years.

Pikselnesia is a more recent studio, releasing its first title, What Comes After on Windows PC via Steam in 2020. A remote studio with a total of seven full-time developers working throughout Indonesia, it was helmed by Mohammad Fahmi, a former employee of Toge Productions.

Sadly, weeks after speaking with Stevivor for the purposes of this interview, Fahmi passed away due to complications arising from an asthma attack. His warm, friendly spirit and passion for not only games, but Indonesian games, was immediately apparent; his influence on the industry was reflected in the massive outpouring of grief and support from game makers around the world.

Fahmi entered the world of video games as both a mobile phone game developer at Gameloft and as a journalist. In the latter stream, he first worked as a freelancer before climbing through the ranks of Tech in Asia, eventually finishing his tenure as its managing editor. He then moved to Toge to serve as a marketing and PR manager before leaving to form Pikselnesia.

The need to pivot

While “pivot” has become a buzzword in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, Indonesian video game developers had to be agile and fluid far before the world’s recent string of lockdowns.

“We never intended to be a publisher; it just happened out of necessity,” Hadiputra reflected. “Back in around 2014 or 2015 – because Flash was not supported on iOS – Flash started dying and we had to pivot our business to find other platforms or other avenues for our games.”

While Toge was able to make the transition to Windows PC via mega-popular digital storefronts including Steam, itch.io and Good Old Games (GOG), others did not.

“We saw a lot of game developers in Indonesia had to shut down their studios because they weren’t successful enough in pivoting from Flash to mobile or to PC,” Antoni said. “It was very sad for us because… our comrades couldn’t survive the game industry.”

Fahmi’s experience was similar, though he came from a background in mobile game development using the Java programming language. The colleagues he was surrounded by created titles for Nokia mobile phones, which sadly met the same fate as Flash.

While Java-based developers could – and did – transition to larger mobile game development, Fahmi said that few were able to find the same levels of success as in the past.

A game about sitting and drinking coffee

Big successes still occurred, and from the most unlikely of places.

Toge’s Coffee Talk was released in January 2020, a low-stress, lo-fi visual novel set in an alternate reality Seattle full of humans and supernatural creatures like orcs, mermaids and elves. Playing as a humble barista, you engage in small talk with your clientele whilst brewing them the beverage of their choice.

Coffee Talk started as an internal game jam project, an annual event in which everyone at Toge Productions gathers to experiment and build potential pitches. Most game ideas won’t make it past the initial stages of development, but every idea is welcome to be pitched and worked on without judgement.

The special event meant then-marketing manager Fahmi could become a developer once again.

“Fahmi pitched this idea of a game; he [wanted] to emulate the feeling of holding a warm cup of drink while looking at the rain outside your window and listening to music and… your friends talk or gossip,” said Hadiputra.

“Who would play a game where you just sit and drink coffee?” Fahmi recalled with a laugh.

As it turns out, a lot of people. Coffee Talk proved to be quite the success, with IGN reporting the title made RP7.6 billion (approximately $726,000 AUD) within less than one month of its release. It also cracked Steam’s top 20 new releases in its debut month, appearing alongside big names like Dragon Ball Z: Kakarot and The Walking Dead: Saints & Sinners.

At the time of writing, Coffee Talk is currently offered at a 32% discount on the Steam marketplace for Windows PC; all proceeds gathered between 1-5 April will be given to Fahmi’s family in the wake of his passing.

Toge has planned a sequel, Coffee Talk Episode 2, for release later this year.

A rainy day, western game

Despite a headquarters nestled along the western border of Jakarta, one of Indonesia’s largest cities, it was never considered as a setting for Coffee Talk.

“It’s too hot, it’s too humid, it’s too busy,” said Fahmi of Jakarta itself.

“It’s a hellhole,” he added with a sly smile. “I love it. It’s my hellhole.”

Jokes aside, Fahmi also pointed out that Coffee Talk began as a concept without a city in mind, meaning one had to be decided upon afterwards. He said that Tokyo was also considered for the game’s setting, as he drew inspiration from the Netflix series Midnight Diner, in which a proprietor operates a late-night diner in the backstreets of Shinjuku.

Ultimately though, Seattle was chosen as it ticked more boxes.

“We wanted to have a setting that had a pretty high precipitation rate,” said Hadiputra, adding that “because Starbucks was originally from Seattle,” it had more appeal than any rainy Indonesian city.

The other factor in the decision, of course, was due to simple demographics.

“If we set it in Indonesia, for example – even though we love Indonesia and we really want to show our culture, our history – the problem would be that a lot of people around the world might not be familiar with that. It might create some barriers for people trying the game,” Hadiputra said.

He also noted that Coffee Talk isn’t without “cultural references in the dialogues or in the drinks that you serve,” including the likes of Jahe Tubruk.

Embracing Indonesia

While Coffee Talk needed to be attached to a city after it was conceived, Fahmi says that his upcoming title Afterlove EP was always created with Jakarta in mind.

Fahmi referenced classic Indonesian film The Raid: Redemption and its sequel, The Raid 2: Berandal, discussing Afterlove EP’s setting. While both Raid films were set in Jakarta, the original really could have been set anywhere. The sequel, however, was so very proud to be set within Indonesia’s capital city and in a way featured it as a character itself. Afterlove EP similarly shows its love for its country, also serving to show how Fahmi’s creative work has evolved.

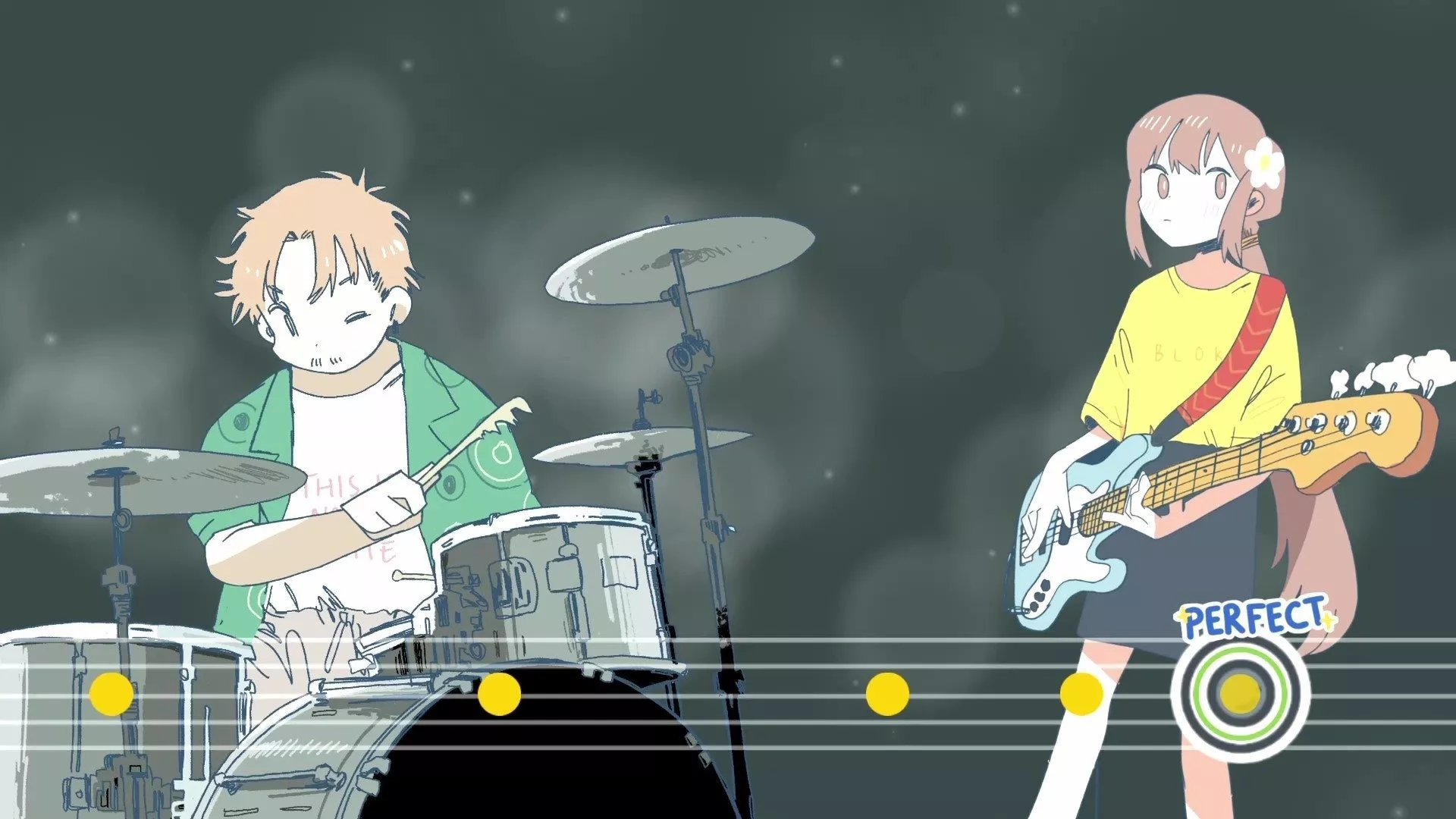

Afterlove EP is more than a simple visual novel, instead a side-scrolling adventure that combines elements of a dating simulation, a rhythm game and a narrative adventure. Players control Rama, a young musician who lives in Jakarta and is dealing with the passing of his girlfriend, Cinta.

Departing Toge with the hope of creating his own games, Fahmi quickly learned that getting a PC game off the ground can be an expensive process.

“We focussed on making something… and started pitching,” he recalled.

“You need money to develop a prototype; you need the prototype to get the funding,” he lamented, adding that he planned to put his life savings into the project.

Thankfully, Fahmi had already caught the eye of Melburnian publisher Fellow Traveller after Coffee Talk featured within its annual LudoNarraCon event, a digital convention that not only showcases narrative video games using the Steam platform, but strives to connect indie developers with opportunities to create.

After reconnecting, Fellow Traveller stepped in and provided Fahmi with an initial round of funding that would translate into a playable demo. The venture proved to be a success, prompting the publisher to fund the full game.

“A big part of the appeal to us was that it was set in modern day Jakarta and reflected modern urban Indonesian culture well,” Fellow Traveller founder Chris Wright said of the project.

Creating local opportunities

While Fellow Traveller formed in 2011 off the back of industry veterans in the triple-A games publishing industry, Toge Productions formed a publishing wing as it went.

Toge “started doing collaboration projects with studios and tried to give more support, maybe by combining our teams,” in the wake of the fall of Flash, Hadiputra recalled.

“Slowly we felt like what we were doing was starting to become like a publisher,” he continued. “In around 2017, we decided to open a publishing division that focused on managing external studios and helping them in terms of marketing, securing funding, promoting or getting onto consoles, or getting dev kits.”

In that same vein, Toge also identified that sources of funding in Indonesia are sparse, stepping in to fill that void with a program of its own.

“The scale is so limited,” Hadiputra continued, speaking of Indonesian government-based sources of funding. “They only accept, probably, ten games per year or something like that. There are hundreds or thousands of developers out there, and there’s only ten of them that can get a very small grant.

“The grants are not big, compared to Malaysia or Singapore,” he continued. “Usually, it’s more towards student projects or something that could promote Indonesian culture or something like that. Because of that, we felt like we needed to give more developers more chances, so we just opened our own program.”

The Toge Game Fund Initiative is a grants scheme that provides up to US$10,000 in funding to a developer while they retain full IP ownership of their product. The funds are intended to be used to build a vertical slice of a larger whole in order to secure more funding, in very much the same way that Fahmi was able to get Pikselnesia’s first work up and running. Toge additionally asks for the right of first refusal on any fully-developed game that could come from the scheme.

Cross-country collaboration

Despite his charismatic, jovial nature, Fahmi approached Indonesian game development from that lens of failure. The word itself – “fail” – came up a surprising amount in our chat, as did an admission that he didn’t expect a second round of funding from Fellow Traveller.

“I became a game journalist… because I could connect and learn from those who had failed,” he recounted, also asserting that he wanted to form Pikselnesia in his 30s and use his life savings in case his game didn’t resonate with players and he needed to start again.

In other words, “now was the time to fail,” he asserted.

He thankfully didn’t need to worry about that; his vision piqued the interest of players around the world and, of course, some sensible investment opportunities.

“[Originally,] we didn’t have many options for funding,” he said, explaining that venture capitalists were at times accessible but didn’t have an adequate understanding of video games or the work involved in development. Most VCs also wanted a percentage of Pikselnesia itself, potentially compromising Fahmi’s work.

As publisher of Afterlove EP, Fellow Traveller not only provides the necessary capital to get the project off the ground, but adjacent tasks like marketing and PR. Services end there; according to Wright, it doesn’t get in the way of the creative process, the developer to work on their core intent.

“The vision is what the developer pitches,” Wright explained. “We help them deliver on what they sold us, but we don’t [do things like] try to change a character.”

Fahmi said he saw Fellow Traveller’s contribution in a different light.

“I didn’t want to do the marketing work anymore,” he said with a chuckle.

Wright said Fellow Traveller’s collaboration with Pikselnesia was crucial, part of its quest to “support diverse voices” and find “unique narratives” including those from across Asia.

“COVID has helped with some of this stuff,” he continued, noting that our newfound reliance on video calling software like Google Meet, Microsoft Teams or the mighty Zoom mean it’s easier to connect and discuss pitches.

“It means that everyone doesn’t have to go to conferences to show their games,” he said, adding that there’s a savings of both cost and time if developers and publishers alike don’t have to plan to attend events like E3 in Los Angeles, the Tokyo Game Show, gamescom in Germany or even PAX Australia closer to home in Melbourne.

Hadiputra agreed with Wright’s assessment, bringing up Fellow Traveller and Pikselnesia without prompting when speaking of the opportunity for increased collaborations between Australia and Indonesia.

“There’s a lot of room,” he said, “either joint ventures, joint projects, co-development, or even just outsourcing. There’s a lot of potential there.”

Failing to success

“Sadly, Flash game sponsorship is now gone, and with that, the financial safety net for starting developers to experiment their ideas to fail – and fail forward – is gone with it,” Hadiputra said of the state of local development, using that one particular word that Fahmi kept repeating.

“I see a lot of cool, new talented new developers having cool ideas across Indonesia, but they don’t have that financial safety net where they can experiment,” Hadiputra continued.

“If they fail then it’s the end for them. Because of that, we feel like we want to have more Indonesian game developers – we want to have more Indonesian games – so that’s why we set up the Toge Game Fund initiative. To provide that safety net so that you can experiment.

“If it fails, it fails; it’s fine. If you learn from your failure, then you can at least make your second game.”

Image at top: A screenshot from Afterlove EP

This article may contain affiliate links, meaning we could earn a small commission if you click-through and make a purchase. Stevivor is an independent outlet and our journalism is in no way influenced by any advertiser or commercial initiative.